A few weeks back I was visiting my youngest daughter. We had turned the TV off and I was just enjoying some civilised conversation with my daughter, son-in-law, grandson aged 18 and granddaughter aged 16. We got on to the subject of coffee breaks and I told them that when we worked out of Holland Park District Nursing Association, we were given two bob (2 shillings) at morning assembly to stop work mid-morning and have a cup of something hot to drink and perhaps a sticky bun. This was considered to be a ‘three line whip’.

“Why gramps?” asked granddaughter. “Oh,” I replied airily, “it was to raise our blood sugar levels to protect us from the TB patients we had to visit after the break.” Disbelief all round. So I explained what the situation was at the time. Those of you of a ‘certain age’ who were practicing District Nurses in the 1940s & 50s will remember it well. Those who weren’t – read on!

Sanatoria beds were full of cases of Pulmonary Tuberculosis and it was a major cause of death. Rates of infection had risen alarmingly during WWII and there wasn’t much of a cure in those immediate post-war days. Patients were sent home to our care and we all, I suppose, ran the risk of contracting the disease. Indeed, despite the crude barrier nursing techniques we employed, some of us actually did!

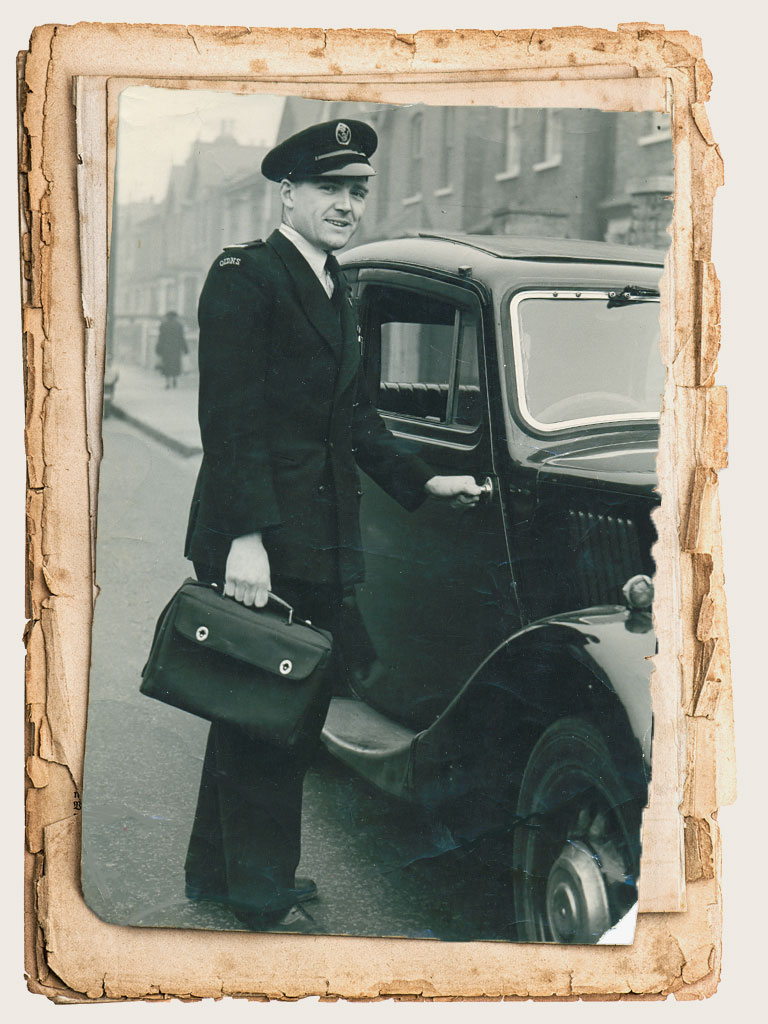

I trained at Kensington DNA in the latter half of 1952. My ‘patch’ for the first 3 months was pretty well the whole of North Kensington and my daily caseload would typically have included 6 patients who needed Streptomycin (‘Strep’) injections. We were all exhorted to leave these till after 11 am when we had spent our 2 bob, and a gang of District Nurses used to descend on a café just off Ladbroke Grove. There was another meeting place in South Ken, in the old ABC Café on Earls Court Road.

TB really was a killer. It was rife between the two World Wars and increased during the Second World War when members of the armed forces were huddled together in billets or messdecks, sometimes under conditions which enabled the Tubercle bacilli to flourish. When I was only about 7 years old, in the mid 1930s, my best friend disappeared one day and a few weeks later, we heard he had died from what was called ”Galloping Consumption”, more properly known as Miliary TB.

In 1953 I moved to Eastbourne, one of two male Queen’s Nurses, and carried on with half a dozen or more ‘Streps’ each day. Most patients had the jab twice a week, though some had it every day. By 1954 I had two daughters and when they went to school in the late 1950 s, it was found that their Mantoux tests were strongly positive, using relatively low levels of the test medium. It was clear that they had been receiving small doses of contact with the bacilli from my clothing, leading to what was effectively an immunisation! Interestingly enough, my other two daughters – born in 1959 and 1963 – had to have BCG immunisations at school when the time came. This, no doubt, because by the time the 1960 s arrived, my contact with TB patients had almost disappeared and I no longer carried bacilli home with me.

This was due to the fact that all over the country, District Nurses had been helping to eradicate TB by their injections – later assisted by the use of two powerful oral drugs – PAS and INH, both of which enabled lower doses of Streptomycin to be used. This was particularly beneficial for children, many of whom, in the early days, suffered permanent damage to the Auditory Nerve from the effects of high doses of Strep. Coupled with the programme of Mass Miniature X-rays, the regime reduced the incidence of Tubercular Disease for years, though now it seems to be on the increase again.

The point of this is to illustrate how we, the mainstay of Community Nursing at the time, were – jointly with our hospital based colleagues – instrumental in bringing about a sea change in the occurrence of Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Great Britain. The disease had almost reached epidemic proportions by the time we rolled up our sleeves, donned our gowns, put our bags on those sheets of newspaper, boiled our syringes and needles and slipped the 5 ml dose into the patient’s rear end. Thousands of us, treating maybe four to eight patients each day. Nice to know we helped to change History in such a significant way, isn’t it?

Geoff Hunt

Queen’s Nurse, 1952