One of the main roles of district nurses in the early part of the war was to help organise the reception of evacuees from London and other cities to the countryside. In West Sussex, one of the ‘reception areas’, the Queen’s Nurses’ magazine describes how district nurses met evacuated mothers and children at railway stations. Children were given medical examinations to determine which needed special care before they proceeded to host families. District Nurses were also responsible for training members of the Civil Nursing Reserve of whom there were almost 100 in West Sussex in March 1940. Nurses also attended a two day meeting in London on Moral Re-Armament, and the health producing value of a positive, fear-free environment.

A Queen’s Nurse Serving in France

In September 1940 Queen’s Nurses’ magazine published a description by an unnamed Queen’s Nurse of her experiences serving with Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service in ‘a port’ in France in November 1939. She wrote:

“We were fortunate in having a fairly good building for a hospital, but one which had not been used for many years, and was thick with dust and dirt. The first thing the sisters had to do was to clean it…The wards were large, and took about fifty-six beds each, until hostilities started in earnest, when each ward had to put up twelve extra…

“We were well staffed, but when winter came there was much sickness among the troops and also unfortunately among the staff… One great drawback to this hospital was no hot-water system, so that when boiling water was wanted for a dozen or so inhalations, four hourly, fifty-six gargles T.D.S. antiphlogistine to be heated, two-hourly feeds to be made, patients to be blanket bathed, everything had to be managed on one very poor gas ring and very ‘tricky’ Primus stove. You will believe me when I say we were kept ‘at it.’ We had the Rubella epidemic of course…

“When hostilities began in real earnest, and people from all over the place were coming through our port after the evacuation of Dunkirk, we had to become a casualty clearing station instead of a base hospital, and send cases fit to travel straight back to England. Several hundred sisters came to our hospital for the night on their way home. Many had lost all their kit. Some whom I knew personally had lost their hospital ship; it went down at Dunkirk. They were thankful for a mattress on the floor to sleep on after many days and nights of harassing experiences.

“Once a week for half an hour we were ordered to work in our gas masks. This was a good idea, but not a welcome one, but it was a humorous sight to see us wearing our veil caps on the top of them… For over a fortnight before we actually evacuated we were told to be ready to leave at a moment’s notice. We were being raided every night. Sometimes two or three times a night we were down in the cellar in the pitch dark with our hand luggage ready for a quick ‘get away’ if necessary.”

Finally the hospital was evacuated without loss of staff or patients.

Costs of Providing Nursing

At home it was also announced that steel hats and respirators were being obtained for all Queen’s Nurses. An appeal for £1000 to buy an ambulance was launched and in the event over £4000 was raised. The Ministry of Health arranges to pay the health costs of all ‘transferred workers’ – those who have been drafted to work in the munitions factories. The rate is 9 pence per nursing visit required. In December 1941 advice is given on the rationing of clothing and how this would affect the Queen’s Nurse uniform. Variations on the standard uniform will be permitted. Under an short piece entitled ‘Human Glow-Worms’ there is a description of a luminous arm band with the word ‘Nurse’ on it for sale for 1 shilling and 6 pence, available from Messrs Lunalite Ltd.

Nurses’ Experiences of The Blitz

The December 1940 issue of the Queen’s Nurses’ magazine records that the Coventry Nurses’ Home and three other nurse’s homes were destroyed during air attacks, with one nurse injured and the mother of another killed.

Another unnamed nurse wrote vividly of her experiences of The Blitz on 7 September 1940 from East London. “The noise, the whistling, the crashing of the bombs was alarming. Passers-by were glad to almost fall into our Home and along to our shelter. Our dining-room was complete with sand bags and other protection, and there we led them. Only two of the nursing staff were in the Home, others were all our on their districts, for it was but 3pm.

“We sheltered for an hour, perhaps a little longer. The house trembled, and with some crashes we felt that the front had gone. We heard the noise of falling buildings, the terrible crackling of the fires, and the unmistakeable smell of smoke. As soon as it was a little quieter we crept out. From the front doors dense clouds of smoke filled the atmosphere absolutely. Then up onto the roof. Never can we forget the sight which met our eyes. Not only smoke, but massive flames, leaping up into the sky. All around us a complete ring of fire – docks, warehouses, schools and gasworks….the cinema opposite to us had gone, and there was a crater at the end of the road…

“The next three days and nights were just continuous hours of bombs, fires, homeless, injured, bereaved, and the night bell pealing to admit still more friends whose homes had fallen around them. So many excellent first-aid posts and the hospitals were all ready, but it was the unexpected number of homeless folk which caused such distress. By Wednesday morning there was a steady stream of refugees homeless, and complete with their bundles and rescued treasures from the ruins of their homes. Meals were served in our duty rooms, and babies were bathed who, with their mothers, had been imprisoned in their Anderson shelters for two days, or even longer…

“Hold tight folks, was the pass-word of the night, especially when the ceiling came upon us, and the lights failed, and the front door really did fall down. We hold on a bit, and then “Are you alright there?” calls a warden. By candle light we decide that we are, and thank him. Out we go. Oh joy! The house is still standing, though not the front door; windows out, curtains and blinds all over the road, houses down either side of us, but no casualties.

“We bring in the homeless and shocked ones, and attend to them, and as soon as it is light, various members of the staff set off for the schools and church halls to help tend and feed the homeless… Tragic are the happenings when new blocks of flats are hit…invariably the trench shelters are wrecked and the walls cave in. Twenty hours, and the rescue squads still digging. One hundred and seventy in the shelter, and all brought out alive but six. The last man, still conscious, and the doctor is near to give morphia. “No, thank you, doc; just a cup of tea, thanks.”

A Patient’s Letter

In a report in January 1942 the Queen’s Nurses magazine prints a letter from a patient as follows (with original spelling):

“Dear Matron – I was blarsted out of Paradise Street, then went to Wymering, then came to Wells Street and was blarsted out again. I am now at Victoria Street, and my leg is very bad, so please send a nuse to do the usual.” The nurse correspondent goes on to tell the editor that they too have been ‘blarsted out’ of their ‘nice convenient Home’.

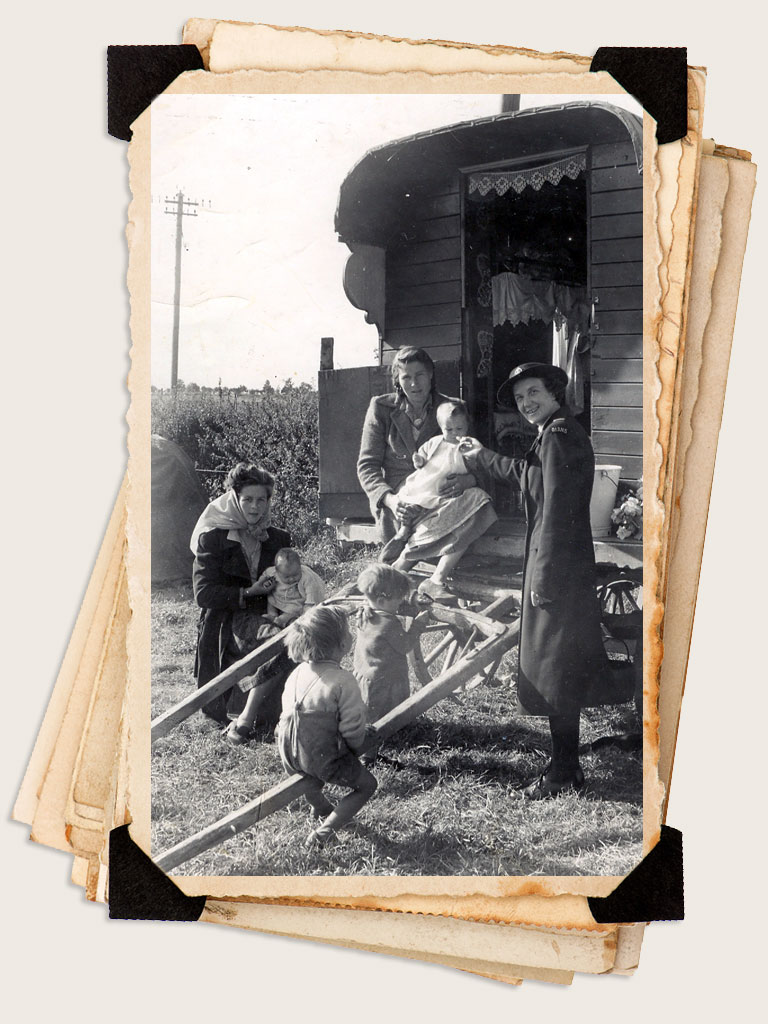

District Nurse visiting a gypsy caravan, 1940s